The study, which used virtual reality headsets to let participants experience the scene, could have implications for custody determinations in criminal cases.

Criminal suspects may feel unable to leave an interrogation room after only three minutes of questioning, according to new Virginia Commonwealth University research.

Hayley Cleary Ph.D., a professor of criminal justice in VCU’s L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, led the study, which used virtual reality to examine how people perceive police custody from “inside” the interrogation room. During an immersive, 30-minute simulated homicide interrogation, study participants wore a virtual reality headset to watch the session, experiencing the scene as if they were seated next to the suspect.

Whether or not a suspect is legally in custody can determine if their statements are admissible in court during criminal trials. Police must read suspects in custody their Miranda rights, including the right to remain silent, before questioning. Incriminating statements made by a suspect who is in custody, but has not been read their Miranda rights, typically cannot be used against them in court.

But it can be difficult to determine if a suspect is formally in custody, especially if they have not been formally arrested. Courts rely on whether a “reasonable person” in the suspect’s position would feel free to leave the interrogation room, but that standard is hard to define. Police and prosecutors may argue that leaving the door open, offering food or telling the suspect they are free to go are enough to make the suspect feel free to leave – a claim that research increasingly disputes.

“Sometimes suspects are questioned for long periods of time and eventually give an incriminating statement, or even a confession, without ever being read their Miranda rights,” Cleary said. “Police and prosecutors often argue – usually successfully – that they didn’t need to Mirandize the suspect because they weren’t in custody.”

But suspects rarely leave during those supposedly voluntary police interrogations, even when told that they are free to do so, most likely due to power disparities and fear of negative consequences.

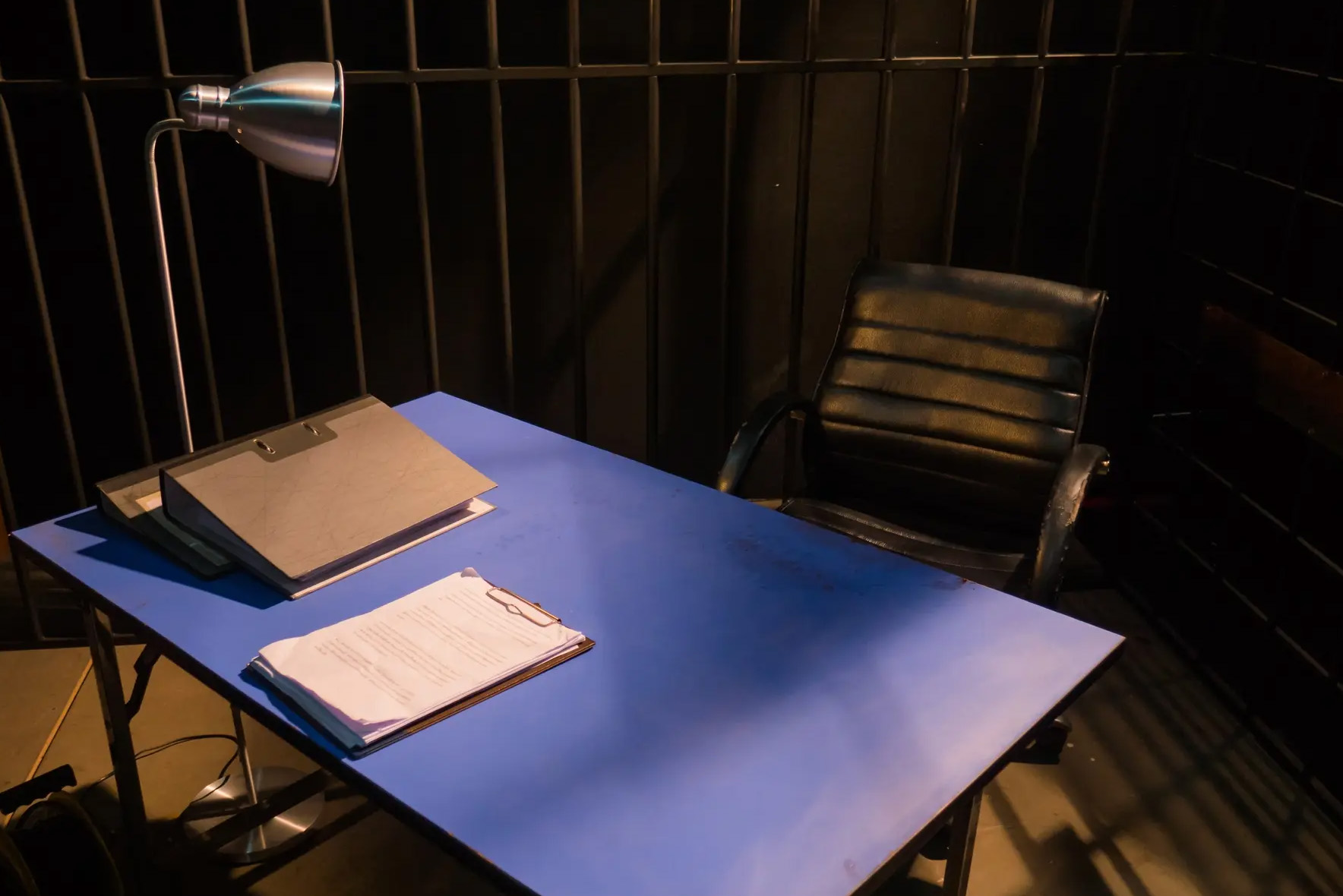

To explore how suspects perceive police custody, Cleary and co-investigator Lucy Guarnera, Ph.D., an assistant professor and forensic psychologist at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, developed VISE – the Virtual Interrogation Subjective Experience project. They filmed a 30-minute simulated homicide interrogation using a 360-degree camera in a local police department interrogation room.

The study was supported by the VCU Presidential Research Quest Fund and featured VCU School of the Arts graduate Joel DeVaughn and Richmond-based actor Doug Blackburn. It enrolled 168 psychologically healthy participants aged 18 to 25, who perceived themselves to be seated directly next to the subject during the immersive virtual reality experience.

Hayley Cleary, Ph.D., associate professor of criminal justice at the Wilder Schoool.

The video, based on a real police interrogation, contained three segments: a three-minute rapport-building section, a 16-minute stress-inducing “maximization” section and an 11-minute “minimization” section, in which the police officer used less aggressive tactics, including explanations and justifications, in an attempt to elicit a confession from the suspect.

The results were striking:

- Over half of the study participants believed that the suspect, whose custody status was not defined throughout the video, was not free to leave the interrogation room after just three minutes of questioning.

- By the end of the virtual interrogation, fewer than 20% of the participants thought that the suspect was allowed to leave the room.

- And by the end, over 90% believed that the suspect himself would not have felt free to leave.

That means that almost all participants thought that the suspect was in custody after only a short period of time, even though he had not been formally arrested, told that he could not leave the room or read his Miranda rights by the police officer.

“Our research shows that simply being in the interrogation room creates a feeling of a lack of perceived autonomy,” Cleary said, who also noted that most police interrogations are longer than the 30-minute video used in the study.

The effect was consistent across most demographic groups. Two groups of participants – those with educational difficulties, and Black participants who reported feeling vulnerable to racial stereotyping by police – were even more likely to perceive that the suspect was not free to leave.

“We found that, across all of these different demographic and background characteristics, our participants converged around the idea that the person that they were sitting next to in this interrogation room did not feel like they could get up and walk away,” Cleary said. “And this effect happened fast. That’s the message that we want legal decision-makers to understand.”

Viewing the video through a virtual reality headset allowed research participants to experience the interrogation far more vividly than by simply watching a video recording or reading a transcript. The findings highlight a gap between what suspects experience and how judges and juries later interpret those moments in court — a disconnect that psychologists call the actor-observer effect.

The researchers were recently awarded $450,000 from the National Science Foundation to expand the project. Future studies will include different police interrogation techniques, biometric measurement of participants’ stress levels and comparisons between different interviewing approaches.